Permaculture

Now You’ve Heard of It, But What the Heck Is It?

Bill Mollison, coined the term Permaculture, and is considered the father of the popular design movement.

Adapted from Modern Farmer by Brian Barth

Maybe the subject came up during a dinner party: “I was just at this permaculture farm and they were planting mashua under their locust trees.” Or maybe a friend just came back from a permaculture course: “Dude, I am totally transformed! I’m moving to Kauai to join a community where they grow jojoba for biodiesel. If I work 12 hours a week, they’ll let me live in a solar-powered yurt!”

So is permaculture a gardening technique or a special approach to farming, like biodynamics? Is it some type of back-to-the-land, off-the-grid intentional community? Is it about sustainable architecture, aquaponics, philosophy, horticulture, design? Permaculture is all that and then some, which is why it’s so hard for anyone to capture what it means in one neat sentence.

Bill Mollison, the Tasmanian son of a fisherman who first coined the term 1978, defined “permaculture” as:

“The conscious design and maintenance of agriculturally productive systems which have the diversity, stability, and resilience of natural ecosystems. It is the harmonious integration of the landscape with people providing their food, energy, shelter and other material and non-material needs in a sustainable way.”

In other words, permaculture is a holistic worldview and a wide-scale technical approach to the land focused on researching, living in harmony with, and harnessing nature’s local ecological synergy. It can be ecological planning, farming, food, and lifestyle combined or any of those approaches on its own.

At its heart, it embraces a social ethos of “Earth Care — People Care — Fair Share” (check out this fun music video), encouraging working with the environment, collaboration, and fair trade. It is a mission aimed at working in alignment with natural principles rather than imposing ideas separate to the natural world.

The name is intended as a blend of permanent and agriculture, which has been expanded to include culture in addition to just agriculture. The root word “permanent” is intended as a reference to sustainability – an unsustainable society would, by definition, eventually cease to exist; it would be impermanent. Practitioners are known as “permaculturists” or “permies.”

Origins + Influence

The father of modern permaculture, as he is affectionately known, Bill Mollison, pictured at top, originally became a professor of bio-geography and environmental psychology at the University of Tasmania, where he met David Holmgren, a graduate student at the time, with whom he developed the principles and practices that are now taught around the world in the standard Permaculture Design Course, typically a two-week immersive experience held on a farm or property that has been developed with a permaculture approach.

Now 88, Mollison, though a warrior by demeanor at times, was quite charming and had a way with words, penning a number of books over the years, including the hefty Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual, which is the bible for the movement. He also starred in Global Gardener, a docu-series made for Australian public television in the early nineties, which is now a cult classic available free online.

Permaculture has grown to become highly influential in the discourse of sustainable agriculture and green lifestyles. Its popularity and benefits have been gaining real ground in both the progressive and mainstream spheres over the years, born of a purpose-driven underground social movement.

I [the author] was a die-hard devotee in my early twenties, eventually earning my Permaculture Teacher’s Certificate and offering courses on everything from designing food forests to building bio-swales on the farm in California where I once lived (in a yurt for which I bartered my labor for rent).

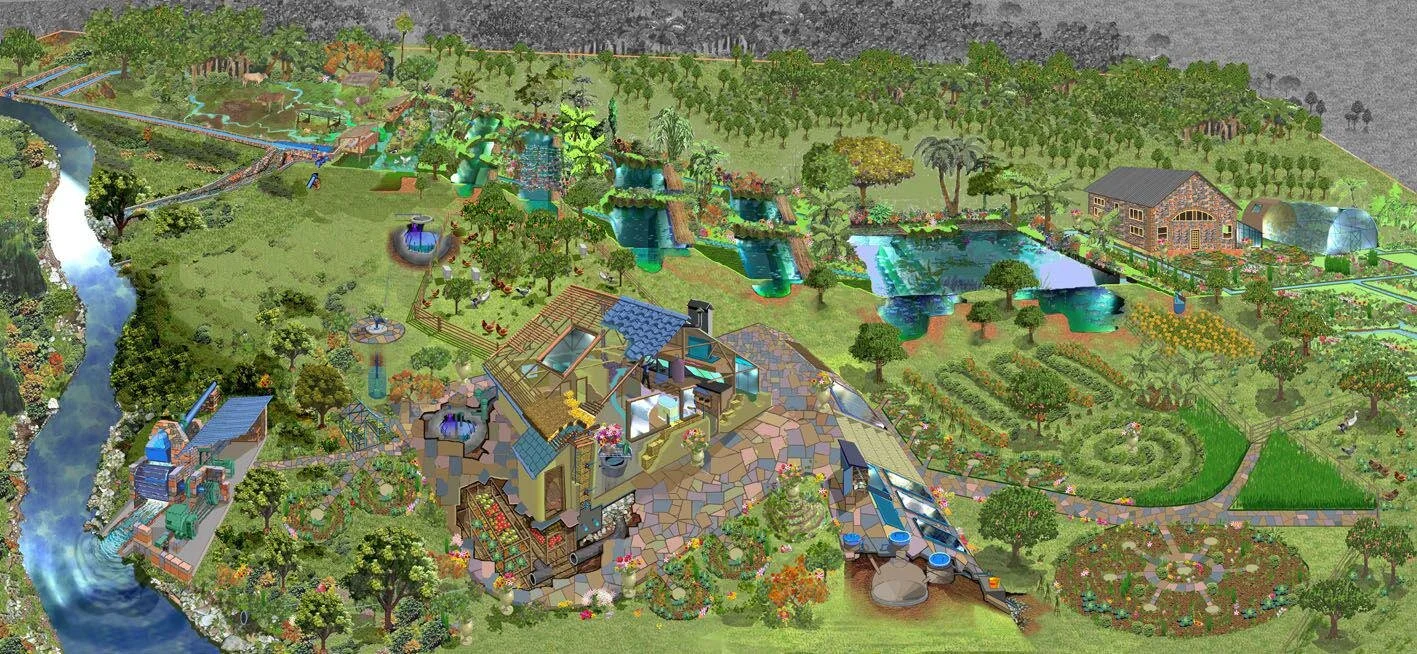

Pictured above is a beautiful example of permaculture principles in action. This iis the Mandala Garden at Le Ferme du Bec Hellouin in Normandy, France, an experiment in how to grow the most food possible, in the most ecological way possible, and create a farm model that can carry us into a post-carbon future—when oil is no longer moving goods and services, and localization is a must.

Though some of its practitioners may be worthy of a Portlandia spoof or post-apocalyptic survivalism with all their talk about herbs spirals and mandala gardens, the proof of permaculture’s influence on the mainstream is everywhere— its basic tenets are embedded in every idea about sustainability that blares from the television or the menu of a farm-to-table restaurant. Here are five of its more well-known principles to help you understand what permaculture is all about.

Here are five talking points to explain sustainable agriculture's holistic cousin

Closed Loop Systems

Any system that provides for its own energy needs is inherently sustainable. This concept can be scaled from things like biofuels and solar power to “inputs” like food and fertilizer. For example, rather than importing fertilizer to a farm or garden, the system could be designed to provide for its own fertility needs – perhaps from livestock manure or cover crops.

And if you’re raising livestock, you should certainly aspire to provide all the food for your animals from on-site, whether raising grain, forage crops, or recycling kitchen waste as animal feed. Any permaculturist worth their salt would remind you that a successful closed loop system “turns waste into resources” and “problems into solutions.” “You don’t have a snail problem, you have a duck deficiency,” Mollison was fond of saying, which makes perfect sense if you’ve ever seen how gleefully ducks wolf down snails.

Perennial Crops

Permies aren’t the only ones to recognize that tilling the ground once or twice a year isn’t particularly good for the soil. Which is why they advocate using perennial crops that are planted just once, rather than annual crops which require constant tillage. Agroforestry, the cultivation of edible tree crops and associated understory plants, is emphasized – think shade-grown coffee or cacao plantations in South America. The only problem is that few crops that most of us eat are perennials; but there is no doubt that if we could replace all the monocultures of corn, soy, and wheat in the world with agroforestry systems (while still feeding the world), agriculture would be much more sustainable.

Multiple Functions

One of the more original ideas of permaculture is that every component of a structure or a landscape should fulfill more than one function. The idea is to create an integrated, self-sufficient system through the strategic design and placement of its components. For example, if you need a fence to contain animals, you might design it so that it also functions as a windbreak, a trellis, and a reflective surface to direct extra heat and light to nearby plants. A rain barrel might be used to raise aquatic food plants and edible fish, in addition to providing water for irrigation. Permies call this “stacking functions.”

Eco-Earthworks

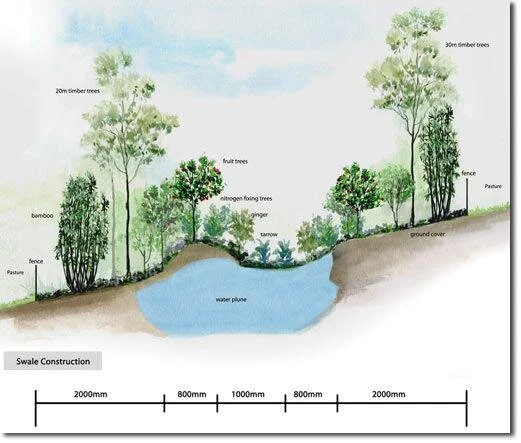

Water conservation is a major focus on permaculture farms and gardens, where the earth is often carefully sculpted to direct every last drop of rain toward some useful purpose. This may take the form of terraces on steep land; swales on moderately sloped land (which are broad, shallow ditches intended to capture runoff and cause it to soak into the ground around plantings); or a system of canals and planting berms on low swampy ground. The latter is modeled on the chinampas of the ancient Aztecs, an approach to growing food, fish, and other crops in an integrated system, often heralded by permaculturists as the most productive and sustainable form of agriculture ever devised.

Let Nature Do the Work for You

The permaculture creed is perhaps best captured in the Mollisonian mantras of “working with, rather than against, nature” and of engaging in “protracted and thoughtful observation, rather than protracted and thoughtless labor.” On a practical basis, these ideas are carried out with things like chicken tractors, where the natural scratching and bug-hunting behavior of hens is harnessed to clear an area of pests and weeds in preparation for planting – or simply planting mashua under your locust trees. Locust trees are known for adding nitrogen to the soil, while mashua, a vining, shade tolerant root crop from the Andes, needs a support structure to grow on. Thus, the natural attributes of the locust eliminate the need to bother with fertilizer or building a trellis, while providing shade, serving as a nectar source for bees and looking pretty. By letting nature do the work of farming and gardening for you, one achieves another of Mollison’s famous maxims: “maximizing hammock time.”